Memories of Messner Shared as Wolverine Football Great Enters College Hall of Fame

Michigan's career sacks and tackles for losses leader enjoyed a good adventure, savored playing defense with exceptional speed, quickness, tenacity and teamwork

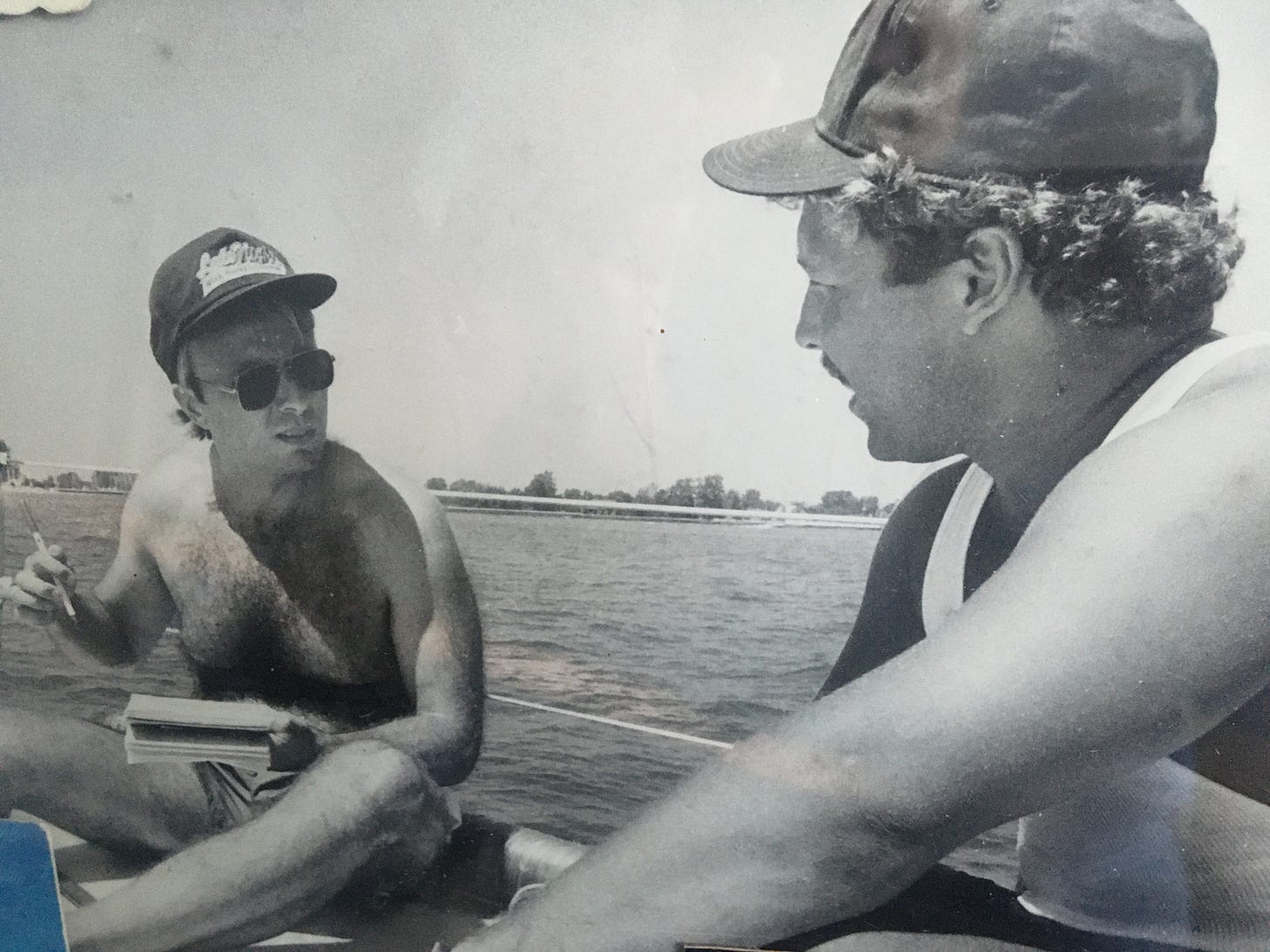

Steve Kornacki interviews Wolverine defensive end Mark Messner on a sailboat in Lake Erie prior to the 1988 season, which ended with a Rose Bowl victory.

By Steve Kornacki

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Mark Messner was announced Monday as a new member of the College Football Hall of Fame, and I texted congratulations to Michigan’s two-time first team All-America defensive end.

He texted back: “Thanks Steve!!! Such an Honor…proud to enter with the Maize & Blue.”

Mark was clearly humbled, but it was a long-overdue honor for a Wolverine whose only defensive impact rivals over the past 40 years have been 1997 Heisman Trophy winner Charles Woodson and 2021 Heisman runner-up Aidan Hutchinson.

He set Michigan’s career records with 36 sacks and 70 tackles for lost yardage that have stood for 33 years, and could stand for another 33 years. Messner spearheaded the nation’s No. 1 defense along with Mike Hammerstein, Mike Mallory and Brad Cochran as a freshman in 1985.

If you find the Big Ten Network playing the 1986 Fiesta Bowl late some night, watch it and you’ll see the best all-to-the-ball unit and hard-hitting defense I’ve ever seen.

We’d gone sailing the summer before his senior year for a Detroit Free Press story, and went swimming in Hanauma Bay near Honolulu after the Wolverines won a game against the University of Hawaii in his sophomore season. We stayed in touch over the years, and he was kind enough to spend the night before the Ohio State game in 2013 signing books with me at the M Den on State Street.

Here’s one of two chapters written about Messner from “Go Blue! Michigan’s Greatest Football Stories,” (Triumph Books, Chicago) with a foreword written by Hall of Fame coach Lloyd Carr:

ADVENTURES WITH MARK MESSNER

Every summer, I tried to visit the home or special place of a Michigan football player entering his senior year. It was my way of taking readers on a unique day trip with one of their favorite Wolverines and showing a special side of his life or interests. Each of those days was a joy because I would discover what made their hearts beat the loudest, and I would meet the family and friends they had talked about for the past several years.

Mark Messner, who earned his second consensus All-American honor and became the school’s first four-time All-Big Ten first-team selection for a Big Ten championship team, took me sailing on Lake Erie a few days before the demanding, draining practices began for the 1988 season. Michigan placekicker and good friend Mike Gillette, Ann Arbor News photographer Colleen Fitzgerald, Messner’s father, and several others boarded the sailboat with us at a marina near Monroe, Michigan.

Being on a 44' sailboat and gliding with the wind has a way of shifting reality. The horizon is so far away that it welcomes the notion that an endless summer really is possible. But the two-a-day practices looming later in the week were a contrast to the peaceful water that Messner and Gillette were all too aware of as they pulled away from the dock. “You go from the relaxing life of golf and sailing to the obnoxious aggression and down-n-dirty world of football,” Messner said. “That’s about the whole spectrum.

“I’m a different person on the field. I’m at work then. It’s two different worlds. But you have to separate yourself for both. People who can’t do that become the stereotyped football player. I hate that image.”

Messner never sits long enough to be labeled. He’s driving across Ann Arbor to rent a Macintosh computer for a business class analysis. Or going through one of those grueling, two-hour off-season workouts. Or rushing to the airport to pick up a friend. Or headed for the links or the lake.

“I cannot stand to just pass time,” Messner said. “One day, all I did was lift and hang out. It was such a long, long day. I wasn’t cut out to be a couch potato.”

On this particular day, Messner was sailing on Outrageous, a pleasure craft owned by his friend, Dr. Stanley Poleck. Nearly a dozen family members and friends were aboard, including Messner’s father, Del Pretty. They gathered at the Toledo Beach Marina for a three-hour spin on the western edge of Lake Erie. The temperature reached 95 degrees, and the deck became hotter as late morning gave way to early afternoon. Time for a dip.

Messner led an “abandon ship” with a cannonball dive off the starboard bow. After a brief swim, the tow line was tossed and everyone who wanted a turn held on for a different kind of a ride. My swimming suit draw-strings weren’t tight enough, and as I was being dragged through the water, the suit came off. I was able to catch them at my ankles and clench tightly for the remainder of my adrenaline rush, saving myself from an embarrassing predicament. When the boat slowed, I was able to pull my trunks back on.

I later told Messner about this, and he could not stop laughing. Two years earlier, I had gone swimming at Hanauma Bay on the southeast tip of Oahu the day after Michigan beat Hawaii. As I got past the white coral reefs of Keyhole Lagoon and swam into the channel, I ran into Messner and receiver Paul Jokisch. We began stroking together, enjoying the warm saltwater on a day when it was freezing cold back home.

But we came upon a metal sign, warning us to avoid dangerous currents by turning back. Messner shook his head and kept swimming out toward the Pacific Ocean, beyond the bay. And we followed, luckily avoiding any problems. Messner was confident there, just as he was on a football field, that nothing could stop him. I thought back to that time in the much cooler water of one of the Great Lakes after my wild ride.

The pull of the tow was hard on the arms but refreshing. “Hey, is this great or what?” Messner asked. The motor that had been turned on to speed up the tow was cut off after 10 or 15 minutes, and the swimming party was asked to re-board ship. Messner, dripping wet, made his way to the mast. He grabbed it, snarled like a pirate and shouted, “Aaargh, mateys!” Someone began singing a Jimmy Buffet song of the sea, and stories of old sailing trips and parties began flowing.

Messner was part of Captain Poleck’s crew in the 1986 Port Huron to Mackinac Race, a prestigious two-day test of navigation, daring, and skill. But more often than not, sailing is a way to reach Grosse Ile for a special dinner, the Cedar Point amusement park, or Put-in-Bay.

“Put-in-Bay is a fun place,” Messner said. “People are having a good time there. But some of them get carried away. There’s this one boat called the Duck Boat that was banned from the island. These guys would do anything.”

There was plenty of down time on the sail, and Messner took advantage of it to talk to everyone and horse around with Gillette. They roomed together off campus and became close. We also had a chance to talk some football and about closing his career on the proper note. Messner entered the season five tackles short of the school record for tackles made behind the line of scrimmage, trailing only the 48 for minus-234 yards set by Curtis Greer, an All-American defensive tackle in 1979.

“Getting to 49 tackles [behind the line] means quite a bit to me,” Messner said. “It’s the only record I really want. To be No. 1 there would be a hell of an honor at a school like Michigan.”

Messner was asked for his favorite tackle. “I don’t really have one,” he said. After some coaxing, the 30-yard chase to sack Northwestern quarterback Mike Greenfield was recalled. His reaction was quite different when asked for his worst mistake. The response was immediate: “Notre Dame. My freshman year. There were two reverses. I got to the play both times and missed. I read the keys properly and just missed them.”

Two mistakes came to mind quicker than 44 big plays. Such is the thought pattern of a perfectionist. For his career at Michigan, Messner shattered not only Greer’s record but the career sacks record set by Robert Thompson, who had 19 from 1979–82. Messner was named the Big Ten’s Defensive Lineman of the Year in 1988 after making eight sacks and setting the school record with 26 tackles for losses.

He is the hands-down most productive front-four player in school history. His 70 tackles behind the line for 376 yards and 36 sacks remain school records through the 2012 season. A quarter-century has passed and schedules have increased from 11 games in his era to 12 games, but nobody has come close to Messner’s numbers. Great players such as 2006 Lombardi Award–winner LaMarr Woodley and 2009 All-Big Ten end Brandon Graham have come up well short of Messner.

The Sporting News had Messner and Bo on the cover of its 1988 college football magazine that summer. The publication ranked the Wolverines No. 1, and Messner held his index finger high as the coach smiled widely in the photo. “People ask me what it’s like to be in Bo’s doghouse,” Messner said. “I tell them that I’ve been lucky. When I got here, Bo said, ‘I have my eye on you. You get out of line and I’m going to come down on you like rain.’

“I guess that fear kept me clean. You find out that Bo knows about everything that goes on on this campus. So the best thing is to avoid situations that can get you in trouble. Bo is intimidating when you come in. But then you find yourself wandering into his office to talk about everything but football. I have to thank Bo and the people at Michigan for developing me as a man and a person.”

Bo was the third father figure in Messner’s life. First was his father, Max Messner, the former Detroit Lions and Pittsburgh Steelers linebacker. But his parents divorced when he was young. Then his mother, Sharon, married Pretty. Messner maintained contact with Max but was raised by Pretty in Hartland, Michigan, just north of Ann Arbor. He called them both Dad.

“It took me an hour and a half to get this guy to bed when he was little,” Pretty said. “Gosh, he was something. You’d have to pin him down at bed time to sit still. He’d make you want to strangle him. All my tools disappeared in the woods with him. Then he went to school and all that changed. The teacher said, ‘Mark is so well behaved.’”

Pretty rolled his eyes. Kids. Messner owned up to the reputation. “I got into everything,” he said. “Mom called me The Pistol. She would say that her big wish was that someday I had a kid just like me. I broke things in stores all the time. It was heaven for me but hell for Mom. When they took me to the beach in Florida, I wore a dog harness attached to a 20' rope.”

The group laughs at the thought. “We can do that now,” said Pretty, stressing the last word and smiling. Messner is hope for every parent with a Dennis the Menace child. Once ashore, I made my way to Bo’s office to talk to him about the menace of his defensive line.

“Messner is a great kid,” Bo said. “He works hard, plays hard, and goes to school. He spends a lot of time visiting kids in hospitals. He’s the kind of kid you want.”

Bo watched Messner all right, just like he said he would. And Bo loved what he saw every step of the way. Messner took out a $3,000 loan that summer. But it wasn’t for a car (his was a 1980 Oldsmobile Toronado that topped 160,000 miles). He wanted to enjoy his last summer as a college kid and “lift weights like never before.”

Maturity has a way of putting its own dog harness on you. Messner realized that. And so there was something more than just that summer slipping away. His college days, days he cherished, were months from conclusion. While Graham (Philadelphia Eagles, first round) and Pro Bowl pick Woodley (Pittsburgh Steelers, second round) were high draft picks who could not match Messner’s college numbers, they thrived in the pros.

Messner, considered undersized at 6'2" and 256 pounds, lasted until the sixth round in 1989 when the Los Angeles Rams drafted him. He impressed Rams coach John Robinson, the former Southern Cal coach who was close to Bo, but Messner played in only four games in his rookie season. Robinson sought for ways to use Messner, a very active “tweener” who was too small for the line and too slow to play linebacker. But he never got a shot at developing.

“My knee injury was a dandy for my one and only football injury— career ender,” Messner said. “Took out my ACL, LCL, and MCL along with my meniscus on the 26-yard line of Candlestick Park versus the 49ers in the NFC Championship Game. Last time I ever put on football gear. Bad day!”

He tore the anterior, lateral, and medial collateral ligaments in the knee, and his NFL career was over. But Messner did well with his degree in business administration and is a market vice president for Konica Minolta Solutions living in Bradenton, Florida.

The photo for his LinkedIn professional networking profile features Messner wearing a sport coat, an open-collar shirt, and a wide smile. On the wall behind him is a framed color photo of Bo on the field during a game, grinning and wearing sunglasses. Bo signed it, “Mark, you are one of my greatest players and a true friend.”

Michigan’s release on Messner’s election:

January 10, 2022

By Dave Ablauf

University of Michigan Football SID

Football’s Mark Messner Named to College Football Hall of Fame

DALLAS, Texas – The National Football Foundation and College Football Hall of Fame announced Monday (Jan. 10) that University of Michigan four-time All-Big Ten performer Mark Messner has been named to the 2022 College Football of Fame Class. Messner is the 33rd player and 39th overall individual from Michigan to be selected for induction into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Messner started all 49 games at defensive tackle for the Wolverines from 1985-88. A native of Hartland, Mich., and Catholic Central High School, Messner holds Michigan career records for tackles for loss (70) and sacks (36), while accumulating 248 tackles during that time frame. He (1987-88) and Brandon Graham (2008-09) are the only players in school history to record consecutive seasons with 20-plus tackles for loss. Messner still holds the Michigan record for sacks in a game with five against Northwestern in 1987.

He was a member of two Big Ten Championship teams (1986 and 1988) and four teams that finished in the top 20 of the final national polls, including the 1985 squad that finished No. 2 after defeating Nebraska in the 1986 Fiesta Bowl. Messner helped Michigan win three bowl games during his time in Ann Arbor: 1986 Fiesta Bowl, 1988 Hall of Fame Bowl and 1989 Rose Bowl. He was also selected as the Co-MVP of the Fiesta Bowl victory over Nebraska.

Messner is one of three players in conference history to be selected as a first-team All-Big Ten performer all four years; Michigan Pro Football Hall of Famer Steve Hutchinson (1997-2000) and Michigan State punter Ray Stachowitz (1977-80) are the other four-time All-Big Ten players. Messner was also selected as the 1988 Big Ten Defensive Lineman of the Year. He was a two-time first-team All-American (1987-88) and was a finalist for the 1988 Rotary Lombardi Award.

After graduating from Michigan, Messner was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams in the sixth round of the 1989 NFL Draft. He played one season with organization before retiring due to a serious knee injury sustained in the NFC Championship Game. Messner is the Market Vice President for Konica Minolta Business Solutions, managing the entire state of Florida for the company.

Messner will be inducted at the National Football Foundation Annual Awards Dinner on Tuesday, Dec. 6, 2022.

Click link below for photo of Steve Kornacki and Mark Messner at 2013 book signing at the M Den on State Street in Ann Arbor for “Go Blue! Michigan’s Greatest Football Stories.”

Steve, you are amazing! There needs to be a special hall of fame to recognize YOU and your writing! Thank you for all you have done throughout the years helping all of us appreciate the talented, humble, hard working, student athletes and coaches U of M has had over the years!!! I aooreciate YOU! 💙💛❤️